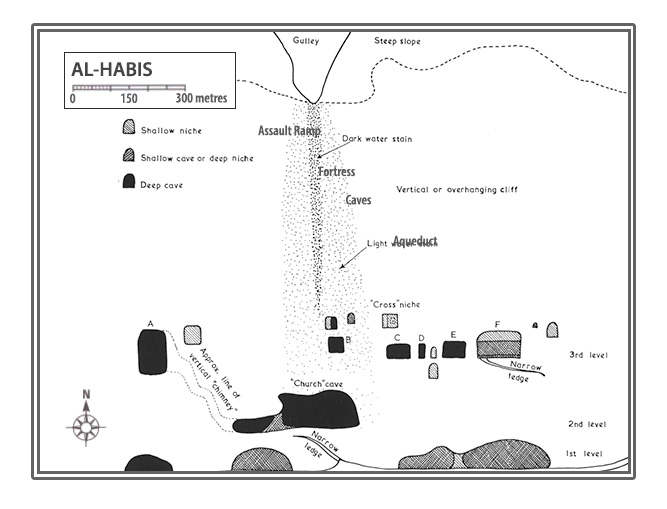

Ledge- and cave fortresses, such as the remarkable Castle Al-Habis (also known as Cave de Sueth), stand as unique examples of medieval ingenuity, relying predominantly on the natural defence provided by their dramatic landscapes. Built by the Crusaders in 1115 AD, Castle Al-Habis was no ordinary defensive structure. Nestled within the rocky cliffs of Petra, the fortress measured an impressive 156.5 by 74 metres. Its strategic location made it exceptionally difficult to access and a powerful means of controlling the region during the Crusader period.

Defences and Structures

Castle Al-Habis’ positioning on steep cliff faces offered natural protection, which was further enhanced by elements such as wooden stairs, ladders, and walkways connecting its three levels of caves. These structures, likely removable in times of siege, added a dynamic defensive capability for the fortress. The chronicler William of Tyre described it vividly as being perched on a vertical cliff, accessible only via a precarious path winding along the mountainside. These caves, he noted, contained living quarters fully equipped with essentials, including a plentiful supply of good water and even space for stabled livestock in the lower levels.

Monuments and Religious Features

Beyond its military function, Castle Al-Habis features intriguing elements hinting at religious and cultural significance. The eastern face of the rock is adorned with unusual monuments, such as the ‘Columbarium,’ whose chamber walls are lined with small, square niches, possibly used for storage or ceremonial purposes. Nearby lies the Unfinished Tomb, a hauntingly incomplete structure that speaks to the ancient artisans’ halted efforts. At the summit of the processional route lies a small high place, historically believed to have served a religious function, adding a spiritual dimension to this imposing fortress.

Siege and Survival

The fortress endured numerous raids, sieges, and exchanges of control across its history.

Nur al-Din’s notable but unsuccessful siege in 1158 serves as a testament to its resilience. However, its defences were not impervious to natural forces; earthquakes, a persistent risk in the region, have caused catastrophic damage over the centuries. Much of the cliff face has since collapsed into the valley of the River Yarmouk, yet several man-made cave structures still remain. Some are astonishingly intact, while others exist as partial ruins or mere recesses in the rock, offering glimpses into the past.

The Craft of Construction

The materials used in the construction of Castle Al-Habis varied, with builders relying on the locally available hard limestone, softer limestone, and volcanic basalt. Each material was selected based on its suitability for different structural needs. Long-distance transportation of stone was rare, reserved only for particular structural or aesthetic purposes. Wooden structures, such as external galleries or hoardings, were likely affixed to the outer walls, though the exact methods remain speculative. These features are reminiscent of similar timber hoardings found in medieval European castles, such as the surviving example at Laval Castle in France.

A Strategic Landmark of Trade and Control

Castle Al-Habis not only stood as an impressive military installation but also occupied a critical position along the trade route from Egypt. This strategic importance made it a coveted stronghold and a significant player in the medieval geopolitics of the region. Despite its current state of ruin, the remnants of this once-mighty fortress still capture the imagination of visitors and historians alike.

Visiting Today

Today, Castle Al-Habis offers a fascinating glimpse into the past. Though time and tectonic activity have taken their toll, the site remains accessible and can be visited en route to Petra’s famed Monastery. Exploring these ruins, with their commanding views and narrative-rich structures, invites you to step back in time and envision the lives of those who once defended these cliffs against all odds.

The story of the Cave de Sueth begins in 1105, when the Crusaders fortified the lower Yarmouk Valley, known to them as Terre de Suethe, derived from the Arabic word sawad, meaning ‘cultivated zone’. This naturally defensible location on the southern bank of the river served primarily as a watchpoint to guard against threats from the east. That same year, however, the Damascus ruler ravaged the area, destroying a Crusader outpost on the Golan Heights. To avoid retaliation, the Crusader Prince of Galilee reinforced the Cave de Sueth rather than constructing a castle on the Heights.

By 1111, this peace was broken as the Cave de Sueth fell to Damascus but was reclaimed by the Crusaders just two years later. It subsequently changed hands frequently, finally being retaken by King Baldwin of Jerusalem in 1118. Thereafter, the Crusaders secured control of the entire Yarmouk Valley, using it as a staging ground for further incursions.

Around this period, another cave fortress, Cavea Roob, was established in the region, likely near al-Mughayir or al-Shajarah. This fortification, located 15km southeast of ‘Ain al-Habis, featured cisterns and remnants of a medieval settlement, further illustrating the strategic value of this fertile yet contested frontier.